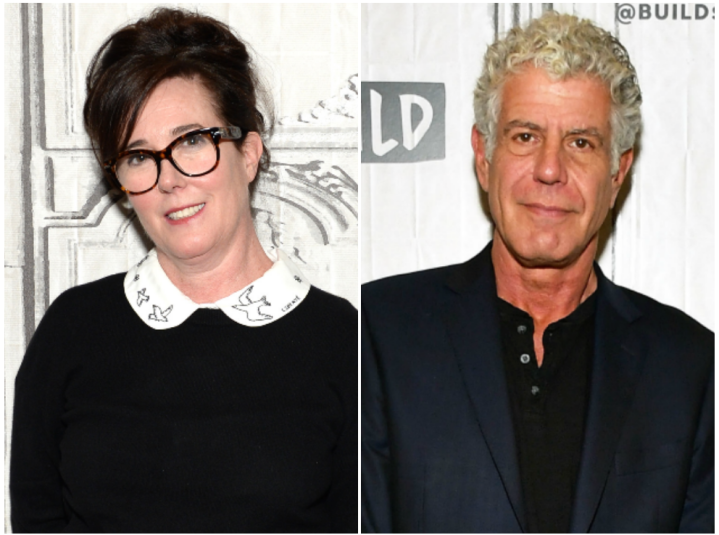

It’s Easy to Vilify Kate Spade and Anthony Bourdain for Selfishness — But Here’s Why We Shouldn’t

Last week was a tough one. We lost two creative visionaries to suicide, and they’re losses that hit hard. Kate Spade and Anthony Bourdain are household names. If you’re into fashion, it’s possible you own a Kate Spade bag with one of her signature playful prints. If you’re a foodie — or even if you just watch CNN regularly — there’s no way to avoid Anthony Bourdain and his gruff, reckless indulgence in food and in life. We saw ourselves in both of them. Their losses feel familiar, maybe a little too close to home, and we’re left to sit in our discomfort, asking ourselves why.

The fact that seems most shocking about the deaths of Spade and Bourdain is that they both left young daughters behind. Some of us find ourselves angry, questioning how anyone could do such a thing to the people they love so dearly; others of us are familiar with the desperation of suicidality and wonder what that says about our identities as parents. All of these feelings are normal.

“Suicide deaths bring up all kinds of emotions that we are unprepared to deal with,” says Jess Stohlmann-Rainey, a peer support line supervisor at Rocky Mountain Crisis Partners. “One of the most challenging is anger. Seeing and feeling the impact of these deaths is so overwhelming. When we are unprepared for our emotions, we become angry that we have to feel them. Frequently, we place this anger on the person who died.”

In the days following Spade and Bourdain’s deaths, I’ve heard people say things like, “But Olivia Newton-John survived breast cancer and a disappearing boyfriend! Brooke Shields struggled with postpartum depression! They didn’t kill themselves,” or, “We all have problems. Suicide is the cowardly way out.”

Suicide is a result of isolation and despair, catalyzed by life events that feel insurmountable to the person affected and complicated by the systems in place around us. The suicidal mind is plagued with a kind of tunnel vision that obscures everything but the unbearable pain it feels. It lies and tells you the people who love you the most — kids especially — would be better off without you. It makes up endless excuses for its lies: You’re a burden, you’re a bad parent, you’re so worthless you don’t deserve to live.

Children are a protective factor against suicide, but the sleepless nights, complicated relationships, and long days can also be major stressors. Mixed with isolation and/or other devastating life events, suicide may begin to feel like an option for some.

“What does that mean for parents? Make sure you have supports in place. Have a plan for what happens in a crisis. Ask for help when you’re overwhelmed,” says Julie Cerel, president of the American Association of Suicidology.

For many, it’s easy to vilify Spade and Bourdain for leaving children behind, but becoming parents doesn’t elevate us to superhuman status. No one is invincible. If you’re still having trouble understanding, try this thought experiment: Ask yourself what kind of pain you would have to be in to consider ending your life. The answer to that question may be the key to finding empathy for those who struggle with suicide.

“Emotions themselves aren’t bad or good, they just are,” says Stohlmann-Rainey. “Having these feelings doesn’t preclude us from also having empathy. We can have empathy and respect the people who we lost. We can feel for the people who are left behind, especially children, who we feel are even less prepared to deal with these situations.”

According to a CDC report released last week, 54 percent of the people who died by suicide in the United States between 1999 and 2016 did not have a known mental health diagnosis. Factors related to suicide deaths cited in medical examiner and law enforcement reports include relationship problems, job or financial problems, substance abuse, loss of housing, physical health problems, and legal problems. Until now, suicide has always been married to mental illness; if you were to talk about one, you had to talk about the other. This report indicates that systemic issues and devastating life events play a much larger role in suicidal despair than we’ve previously been able to acknowledge, which is why empathy is so integral to our ability to understand our emotional responses to deaths like these.

Kate Spade and Anthony Bourdain were rich and famous, but that didn’t make them immune to suffering. Both had a history of struggle. Bourdain, in particular, was very open about his experiences with substance use/abuse and suicidality — key risk factors for suicide. In the end, suicide doesn’t discriminate. It affects people from every possible walk of life — including parents, and especially folks from middle age on.

6 Ways You Can Help Yourself and Others Struggling With Suicidal Thoughts

Knowing that, what can you do, as someone deeply affected by these deaths?

- Learn about the risk factors and warning signs for suicide. If you want to go a step further, get trained in crisis intervention.

- Learn and use appropriate language around suicide. The commonly used phrase “committed suicide” is problematic because it implies sin, crime, or pathology. Instead, experts suggest phrases like, “died by/from suicide,” “took their life,” or “ended their life.”

- Be informed regarding how to share news like this with your networks. Many media outlets are doing a great job with their reporting; others are focused on sensationalism instead of productive, informative discussion about this important public health issue. Avoid sharing articles that mention the method of suicide and explicit details surrounding the death, including graphic photos or the content of suicide notes.

- Get involved. Volunteer your time or donate to a suicide prevention organization.

- Know that, if the constant coverage of these deaths is upsetting you, it’s okay to step away from social for a little while to practice some self-care — whatever that may look like for you.

- Talk to the people around you. Stay vigilant. Ask for help when you need it.

If you’re feeling suicidal, reach out. If you’re not, learn your local and national suicide crisis resources anyway. Share them widely — and then save them in your phone, because there will probably come a time when someone you know personally needs them. You can reach the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255. You can get Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741. The Trevor Project’s hotline is at 866-488-7386 (they also have text and chat services). Trans Lifeline is at 877-565-8860. These resources are available for those in crisis as well as those who love them.

This post was written by Dese’Rae L. Stage, an award-winning artist, public speaker, and suicide-prevention activist. She created Live Through This, a multimedia storytelling series that aims to reduce prejudice and discrimination against suicide attempt survivors. Live Through This has received media coverage from TIME, New York Times, and CBS Evening News. Dese’Rae is featured as the main character in a documentary about suicide-prevention advocates called The S Word, now screening nationwide. She lives in Philadelphia with her wife and son.

More From FIRST

How Do I Know If My Teen Is Depressed? An Expert Answers

Meeting Anthony Bourdain Taught Me the Importance of Being Outgoing

Gillian Anderson Reveals Heartbreaking Battle With Depression